Sunlight dancing on the blue water glimpsed through the trunks and branches of the trees foresting the banks of the river was entrancing. I was surrounded by the lakes and waterfalls of the Krka River in the Krka National Park. An area that encompasses the river basin as it flows through the Dalmatia region of Croatia towards its estuary that flows into the Adriatic Sea at Šibenik. This area is what is known as a karst landscape. Water flowing over rocks of different hardness erodes them at a different rate creating caves, sink holes and terraces.

The components of this particular karst landscape are made from a material known as travertine. Travertine terraces are created through the combined action of physical and chemical factors interacting with living organisms in the water. The action begins the rocky, uneven areas of the flowing water. As water splashes against these areas the balance of the chemicals that make up the water is disturbed and carbon dioxide is released precipitating calcium carbonate (limestone) on objects under the water including moss, algae and fragments of shells. These deposits grow layer upon layer of calcium carbonate and organic material eventually forming barriers or terraces of travertine over which the water cascades forming waterfalls. There are seven of these waterfalls in the Krka National Park and each one is different, from Manojlovac slap, the tallest to Skradinski buk the largest.

Skradinski buk waterfall is the most famous and the longest waterfall on the Krka River. Its series of travertine barriers, islands and lakes can be seen by visitors from a network of paths, bridges, boardwalks and viewing terraces. Our guide took pity on us and lead us against the flow so we only walked up three hundred steps and down eight hundred. Despite the many notices warning visitors not to do this no-one said a word. It also meant that we avoided the crowds at the most popular viewing points. The sight of frothing water crashing over grey rocks and tumbling into an azure pool below was mesmerizing and compelling. We viewed them from every angle possible. There are places where visitors are allowed to swim but we preferred to keep walking and admiring.

Boardwalks weave their way through natural forest vegetation and other different habitats where a huge diversity of plants flourish in this protected area. Three different types of forest dominate this river basin and although they do not cover vast areas they are an important part of a diverse landscape that also includes wetland habitats, grasslands and rocky areas.

In bygone days the power of these waterfalls was harnessed for industrial purposes. Old watermills can still be seen by the river and are open to visitors. There have been water mills on the banks of the Krka River since the fourteenth century, probably earlier. These mills were vital for the economy of the Adriatic coast from Dubrovnik to Istria. Wheat was milled here until the early twentieth century. The watermills at Skradinski buk are the best preserved and have been restored so that visitors can appreciate their historic importance to the economy of the area. The mills on this site were probably built at the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth century. The walls were constructed from stone and travertine using a combination of limestone with sand or clay as mortar. Wood was used for the interior and the roof which was often covered with stone slabs. These mills followed the lay of the land and sometimes incorporated rock faces and caves.

One process carried out in these mills was the fulling of cloth one of the processes in the making of woollen cloth. It involved cleansing or scouring the wool to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, and then making it thicker. Originally fulling was done by a fuller who pounded the woollen cloth with his own feet, hands or a club. Sometimes the women would sing songs to create a rhythm. Increasingly, during the middle ages fulling was carried out in a water mill. It was then followed by stretching the cloth on large frames known as tenters. The cloth was attached to these frames by tenterhooks. Hence the phrase, being on tenterhooks that is, held in suspense. The cloth was then thickened by matting the fibres together to strengthen it and increase its waterproofing or felting. This matting was achieved by hammering the cloth to make the microscopic barbs on the wool fibres hook together. Finally, the cloth was rinsed in water to get rid of the foul-smelling liquid used during cleansing. In Roman times this was stale urine that was so valuable it was taxed! The hammers that were used to thicken the cloth can be seen in a cave that forms part of the Gornja kuća or Upper House of the water mill at Skradinski buk. Gushing water would hit the top of a beam that turned the two strong wooden hammers that pounded the cloth. This cave also features the old washing holes where the cloth was washed and softened.

On the ground floor of the watermill at Skradinski buk there are six restored mills. In these mills barley, wheat and maize would be ground to produce flour and polenta. The grains were crushed between two millstones. Both these huge circular stones had rough surfaces and one of them revolved while the other remained stationary. These millstones were driven by the force of water rushing down the six ducts that carried the water from the mill pond next to the mills. Also inside this building is the kitchen, the miller’s flat and the stables.

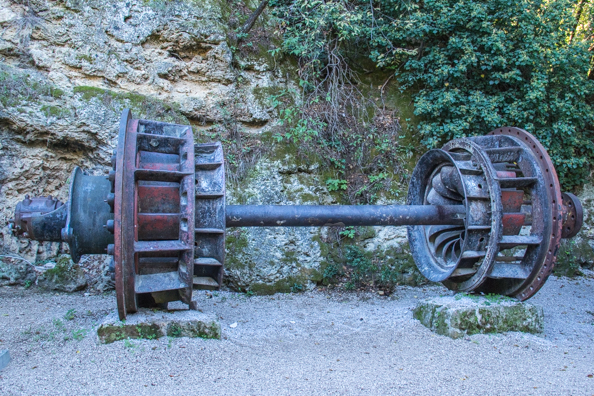

In August 1895 an historic event occurred on the banks of the Krka River with the opening of the Krka Hydroelectric Plant. This happened only two days after the first electric generating plant at Niagara Falls began operating. It was the first transmission of an alternating current at a significant distance in Croatia and suppled electricity to the town of Šibenik thirteen kilometres away. This event is marked by a permanent exhibition in the Krka National Park. Now known as the Jaruga Hydroelectric Power Plant it was one of first hydroelectric power plants in the world and the first of its kind in Dalmatia and Croatia. It was constructed here thanks to the vision of Ante Šupuk a Croatian engineer and inventor and also mayor of Šibenik at the time. In 1893 Ante Šupuk and a member of the city council, Vjekoslav Meichser started a business and obtained a license to use the waters of the Krka River. In 1894 they obtained permission to set up electrical power lines on municipal property in order to start lighting the streets with electric power. Jaruga was based on the work of Nikola Tesla, using his alternating current system patent. Not only did Ante Šupuk supply electricity to three hundred and forty street lights and some houses in Šibenik. He also introduced the Croatian language in schools, built the port, the railway, the aqueduct, a sewage system, a hospital and paved the streets. No wonder he held office as mayor for thirty years. The original power station has been modified several times but it is still operational and part of the unified electrical system of Croatia. Outside the museum is the old turbine from the original Jaruga power plant.

There is so much to see in Krka National Park it is worth spending a day here in order to do justice to the nature in the park, the historical buildings and the souvenir shops selling traditional handicrafts. And have time to relax over a meal in the restaurant by the mill pond.

************************************************************************

Getting there

I visited Krka National Park while staying in Vodice during a trip organised by Solos Holidays. We flew from Gatwick to Split with Norwegian Air.